Dr. Sharon Byrd, 76, is an experienced radiologist in Chicago, Illinois. She has an impressive background, having served as the former chairperson of the Department of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine at Rush Medical Center and Rush Oak Park Hospital. Dr. Bryd earned her medical degree from Wayne State University School of Medicine and has practiced medicine for over 52 years. Her dedication to the field is evident in her long-standing career and her commitment to providing the best care for her patients.

She says her mother obtained a degree in education from Tuskegee University, after which she returned to Honey Pack, Mississippi. However, due to the discriminatory attitudes of the white population in the town, she was unable to find a job as a teacher or even assist in the construction of a schoolhouse for the Black community. In the end, the only option available to her mother was to work in the cotton fields. This was a difficult and unjust situation, but Dr. Bryd’s mother was determined to persevere and make the most of her circumstances.

My mother lived in this small town in the South called Honey Pack. They decided to put their money together and send her to college. The ultimate plan was for her to teach the kids how to read and write. George Washington Carver was her professor at Tuskegee University.”

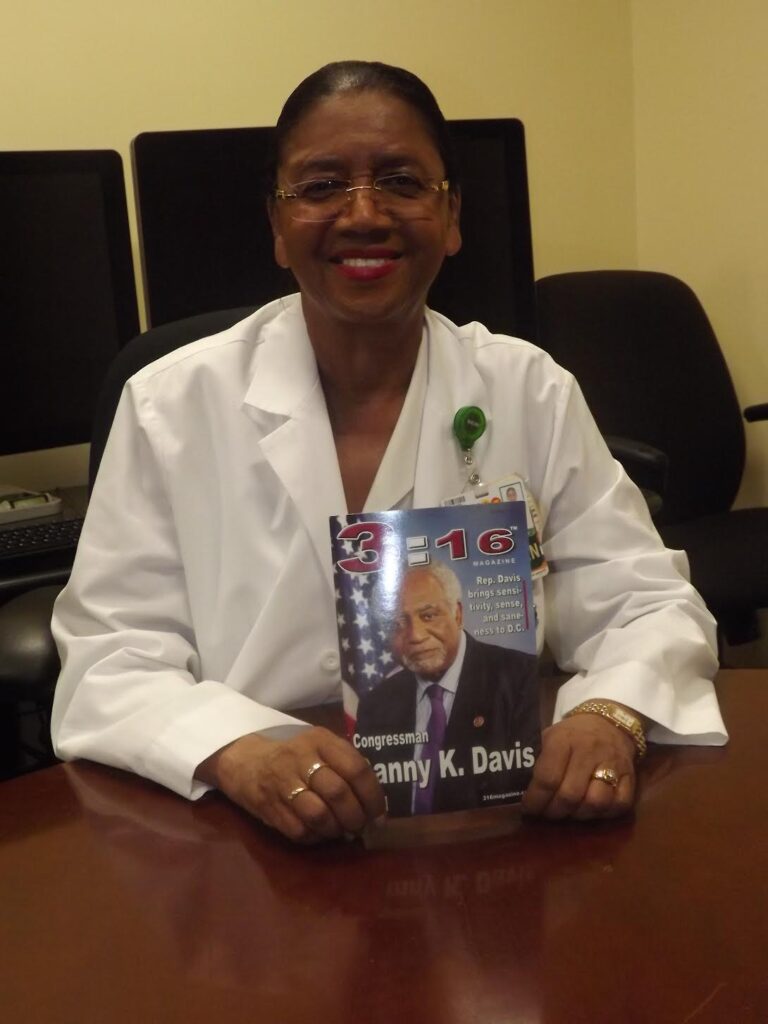

Dr.Sharon E.Byrd.

“My mother lived in this small town in the South called Honey Pack. They decided to put their money together and send her to college. The ultimate plan was for her to teach the kids how to read and write. George Washington Carver was her professor at Tuskegee University,” explained Dr. Byrd.

During the evening, in the cotton fields, the ground is plowed, so she would teach. Her mother’s creativity and resourcefulness in teaching the children in the cotton fields using the soil as her chalkboard was remarkable. She did that for several years. Unfortunately, she had to flee town when her teaching methods were discovered by whites.

“My mother relocated to Detroit where she met my father. They got married and started a family. My dad was recruited at 16, by the Olympic runner Jesse Owen on behalf of Ford Motors. He worked there for 70 years. “

Growing up in Detroit, Michigan during the 1950s and ’60s, Dr. Byrd witnessed firsthand the flourishing of black professionals in their respective positions. Thanks to the thriving automotive industry, a robust Black middle class emerged, providing ample opportunities for African Americans to succeed and thrive. Despite the challenges they faced, many broke down barriers and achieved great success, serving as inspiring role models for future generations. Dr. Byrd remains grateful for these examples and strives to carry their legacy forward.

“There were areas of segregation that included black doctors, lawyers, teachers, and store owners. At that time, Detroit’s educational system was magnificent due to the population being predominantly Caucasian. The Detroit community influenced my life by the environment of professionalism and people of substance, which aided me to become tenacious in achieving my education as a doctor. Moreover, the desire to help Black people in the community, helped me focus on my purpose why I want to become a doctor,” provided Dr. Byrd.

Born in 1946, the oldest of her siblings, her responsibility in achieving was expected with no negotiating. Dr. Byrd attended Detroit Technical High School, a mostly White institution that offered college-level courses and was rated as one of the best public schools in Detroit. Having graduated from there, she proceeded to Wayne State College.

Dr. Byrd confessed, “At that time, college was not expensive. I obtained a scholarship from the APA Kappa AFA sorority for my undergrad and they paid for all of it. Furthermore, I entered medical school while home in Detroit to reduce my expenses. Moreover, I worked as a lab technician and weekends worked in the hospital to obtain an excellent education in medical school.”

After experiencing the effects of the recession in the auto industry in Detroit, Dr. Byrd decided to pursue new opportunities by applying for an internship at UCLA in California.

“I was accepted at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and decided to study radiology. People ask why radiology. My middle sister is a pediatrician, and she informed me that this field would be challenging where you put all the clues together from studying imaging.”

Radiologists like Dr. Byrd use imaging to gather information about the structure and function of the human body that may be unavailable without surgery. They rely on penetrating radiation, such as X-rays, CT scans, and PET scans to diagnose diseases.

In this field, women were discouraged from entering because of radiation. However, Dr. Byrd was not accepting their narrative, and she pursued her desire and was accepted into the radiologists’ program, regardless of the lack of women in the field. UCLA Diagnostics Radiology had one Caucasian woman already in the program; she was the second woman, the first Black. Also, there was one black male in this field named Dr. Collins who passed away earlier this year.

When attending lectures at UCLA, people were surprised to see a person of color. Principles she learned from her parents, working hard and taking accountability for herself, brought favor to Dr. Byrd by others helping her to write papers, publish works, and learn how to articulate herself when talking at the medical society meetings. This guidance and support helped Dr. Bryd achieve her goal of being successful in the program and ultimately, to assist black people and the underprivileged.

Dr. Byrd completed UCLA in 1976 and decided on neuroradiology, one of the hot specialties. In addition, neurology was a difficult career, regardless of gender or nationality. People mentored and supported her because she was a resident and published at UCLA. Moreover, they referred her to Dr. Derek Nash, a pediatric neurologist in Toronto, Canada, who ran the neuroradiology scholarship program.

“Dr. Hannay at ULCA encouraged me to call Dr. Nash, who was an acquaintance of his. Previously Dr. Hannay had talked with Dr. Nash on my behalf and gave Dr. Nash an awesome recommendation for me. I called Dr. Nash, applied for the program, went to Toronto, and got accepted. However, this would have never happened for a female and black in the United States. Also, I needed a program director to sponsor me. Because of my gender and ethnicity, no program director would accept me in neuroradiology in America.”

Dr. Byrd contacted Dr. Nash, went to Toronto, and applied for the program. Besides, Dr. Nash accepted her into the pediatric neurologist program in Toronto, close to Detroit, which allowed her to visit family and friends.

“People felt that Dr. Nash would be prejudiced toward me because he was originally from South Africa. And that would put me in a position where I could not complete the pediatric neuroradiology program. But to my amazement, this one-year program was the best experience of my life. Dr. Nash was very supportive; he taught me almost everything he knew in that field,” exclaimed Dr. Byrd.

“They wanted me to stay after graduation, but I had decided to accept a position in south central Los Angeles at one of the county hospitals just after the Watts Riot in August of 1965.”

The Watts riots resulted in the deaths of 34 people, more than 1,000 were injured, and $40 million in property damage.

“One of the reasons for the Watts riots was due to lack of medical healthcare institutions in the community so they created a county hospital that was named Martin Luther King Junior General Hospital. Which supports a medical school, and they were hiring physicians for those positions. However, doctors didn’t want to work there due to the hospital and medical school location and the after-effects of the riots,” Dr. Byrd said.

She accepted that position at King Drew Medical Center, also known as Martin Luther King Jr., as the head of their neurology and radiation department, with the credentials that she had obtained. However, Harvard and other large well-known institutions had offered her positions.”

“But I decided to decline because one of my goals was to give back to the black community and make a huge difference there. In addition, black patients realized that black doctors had earned the qualification to be in those positions. I was comfortable involving myself in the community by organizing and teaching radiology, medicine, and healthcare lectures. The medical director and hospital administrators were black, very supportive, and flexible to the staff and patients because the riots were the results of this hospital,” stated Dr. Byrd.

One of the disadvantages at King Drew Medical Center, a county hospital, was always getting leftover equipment compared to the largest hospitals in Los Angeles. Dr. Bryds says everyone received new imaging equipment at the time it was needed. They got the best technology including CT scanners; all the other counties’ hospitals had CT scanners, including Big County, but not at King Drew. Eventually, they petitioned to obtain one, and finally, they got it.

Eventually, they closed King Drew Hospital because of financial constraints and re-opened it as an outpatient clinic. “King Drew was like a stepchild to me, and they did not treat it the same after reopening, so I contemplated going to another medical facility to work. King Drew, had support and control from the people who contributed the money,” Dr. Byrd explained.

This medical school was set up for the first two years and was for undergrad in the medical school at UCLA. The last two years were internships at King Drew. Moreover, it was a win-win situation for medical education for the students and clinical experience that gave them hands-on training at King Drew. I was on many committees, but this particular one, the King Drew Medical School admissions committee, had opened Dr. Byrd’s eyes.

“I’ll never forget it. Black candidates, while interviewed, had a grade point average of 1.9 and lower. My mind wandered, Wow!

How could this be when applying to any medical school? Blacks that had applied to these medical schools like the University of Pennsylvania and other high-end medical schools were being accepted. My mind went into overload thinking then it dawned on me about affirmative action.”

“The foundation of affirmative action was good in theory. However, some corporations found loopholes when putting it into action to FAIL. The foundation of affirmative action was not implemented, These particular institutions chose Black people with low GPAs of 1.0 or 1.9 to enter the medical field program, knowing that this would set them up for failure coming into the program.”

On the other hand, Dr. Byrd says they would not choose Blacks with 3.0 GPA averages and above who would excel in the program as they did the white people.

“Yes, at one time, affirmative action did work when used correctly. Also, scholarships were available for minorities. Now there are fewer blacks in nursing and the medical industry. They have found a way to get around affirmative action, and it’s just a system, Dr. Byrd explained.

She accepted a position at Rush Medical School in Chicago, Illinois, after the re-closing and re-opening of King Drew. Additionally, the tuition at Rush is expensive for medical school, approximately 300,000 to 400,000, which does not cover housing expenses.

“My medical education was $2,000 a quarter, and there were three or four quarters. In addition, I came out of medical school debt-free because of what my parents install within me to work hard and be accountable,” provided Dr. Byrd

She believes education for black people should be free of charge due to the mental anguish they have been through the last 400 years. Dr. Byrd says the parents should encourage their children to work hard and get involved in after-school programs that would teach them basic school aid.

Dr. Byrd’s experience was instructing aspiring doctors in algebra, chemistry, and physics at Wayne State. Nevertheless, the current situation presents significant challenges due to electronic courses. She says the students are now receiving virtual instruction and are facing difficulties obtaining prompt responses to their inquiries.

“I love the medical field and what I am doing. Besides that, I am working with a team of physicists who are writing papers on AI artificial intelligence, and we are developing things here at Rush Medical Center. This keeps you stimulated and going with the new generations that are coming up. And one of my desires is to instill in them some work ethics, core values on how to treat people, and also some tips on being honest is very important.”

Dr. Byrd is not just a radiologist who sits behind a desk in a dark room and reads cases. This field is exciting and constantly changing in technology. Every month there’s something new.

Furthermore, one of the reasons she came to Rush Medical Center was a commitment to diversity, and the field of radiology needs more radiologists to care for the patients here at Rush. But it’s difficult because minorities don’t want to go into radiology.

“Plus, Blacks built this nation and were never respected or given the same opportunity as other ethnic groups. Moreover, the civil rights movement started with us, the blacks, and other ethnic groups benefiting from its results,” Dr. Byrd said.

According to Dr. Byrd, the medical field is a microcosm of the communities and cultures it serves. It is a small group of individuals who have the power to impact the health and well-being of their patients. With this responsibility comes a duty to understand and empathize with the diverse perspectives and experiences of those they treat. By doing so, medical professionals can better serve and represent the needs of their communities.

Dr. Byrd explained, “Some people are racist and have problems with minorities. Some respect ethnicities and believe in equality. On top of that, we have people who judge based on the latest news headlines. There are real issues in the medical field. I think you are not treated the same as an African American. They have a concept of binding everyone together and not thinking about individualism because we are all different.”

She has noticed that there are times when people look at me differently, even though they are friendly and respectful. It made Dr. Bryd wonder if they questioned her qualifications or abilities. However, She refuses to let those doubts hold her back. Persistence and determination help her make a positive impact and gain the respect and confidence of those around her.

Dr. Byrd said, “When I became chair at Rush Medical Center, the qualifications for selecting the position were the same regardless of department. They had interviewed people from Harvard, Yale, and other places for the chair. Furthermore, the Dean of Rush informed me that my qualifications were just as good or better than most they had interviewed.”

Finally, Dr. Byrd never understood why Black people must endure so much to get a prestigious position. While going through the process of getting this position, one must manifest dignity, ethics, pride, and responsibility.

“People will dish out stuff, and you will go through situations to accomplish your goals. And remember, when you see black women or people in important positions in society, they have earned it through hard work. The objective is to treat people the way you want to be treated,”